Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Simple Seeing

‘If psychologists can really identify something that deserves to be called perception without awareness, they must have an operational grasp on not only what it takes to perceive something, but on what it takes to be conscious of it.

Dretske, 2006 p. 148

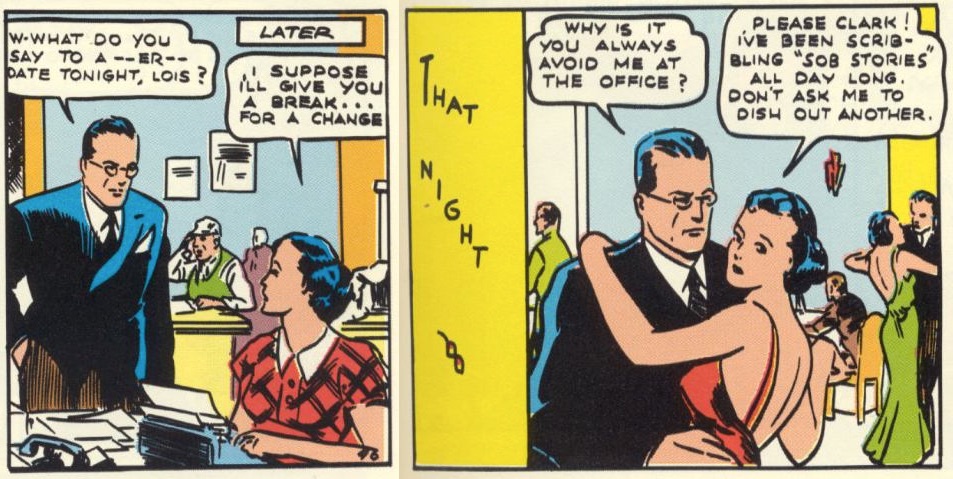

Siegel & Shuster, 1939 (Issue 1)

Siegel & Shuster, 1939 (Issue 1)

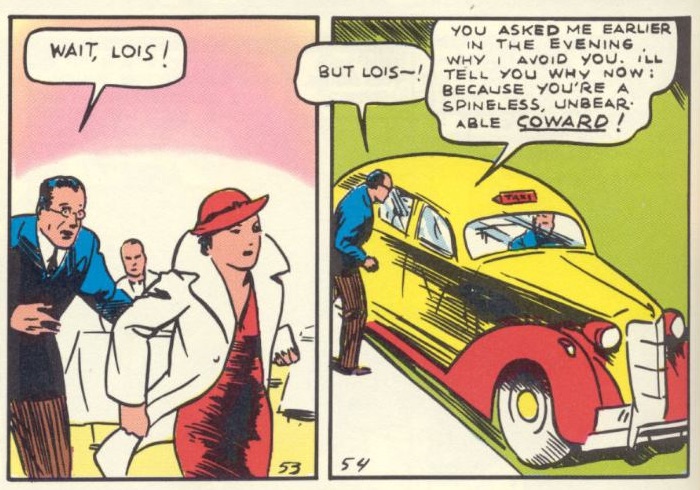

Siegel & Shuster, 1939 (Issue 1)

Does Lois see the unbearable coward?

Does Lois see the unbearable coward?

1. Lois sees Superman.

2. Superman is Clark.

3. Clark is the unbearable coward.

Therefore:

4. Superman is the unbearable coward.

Therefore:

5. Lois sees the unbearable coward.

1. If Lois could see the unbearable coward, she’d know where he is.

2. Lois does not know where the unbearable coward is.

Therefore:

3. Lois cannot see the unbearable coward.

Simple Seeing (aka Nonepistemic Seeing)

Key characteristic of simple seeing: if X is the F, then S sees X is equivalent to S sees the F.

Dretske, 1969 chapter II; Dretske 2000 chapter 6

‘If psychologists can really identify something that deserves to be called perception without awareness, they must have an operational grasp on not only what it takes to perceive something, but on what it takes to be conscious of it.

Dretske, 2006 p. 148

Siegel & Shuster, 1939 (Issue 1)

Can you perceive something without being perceptually aware of it?

‘Perception without awareness [...] is therefore to be understood as perception of some object without awareness [...] of that object’

Dretske, 2006

‘Here lies the fatal flaw in [...] the philosophy of mind,

for, in using as evidence what seems reasonable or persuasive, philosophers ultimately rely on their own introspections.

They look inside themselves

in an attempt

to discover the design of the mind’

Bridgeman, 2004 p. 380