Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Lecture 16:

Central Themes

\def \ititle {Lecture 16}

\def \isubtitle {Central Themes}

\begin{center}

{\Large

\textbf{\ititle}: \isubtitle

}

\iemail %

\end{center}

\section{The Question}

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

\citep{Davidson:1971fz}.

‘The problem of action is to explicate the contrast between

what an agent does

and

what merely happens to him‘

\citep[p.~157]{frankfurt1978problem}.

[Frankfurt] Do spiders have intentions?

[Bach] When I duck to avoid a flying object, am I acting on any intention?

There are theoretically coherent ways of characterising intention on which the answers are yes.

Intentions as representations which somehow guide actions.

There are theoretically coherent ways of characterising intention on which the answers are no.

Bratman on intentions as elements in plans.

We have no way (so far) of distinguishing which among several theoretically coherent

possibilities is correct.

But why are we asking these crazy questions in the first place?

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

Davidson’s View

It is intention (or justifying reasons).

Objection:

Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders [??]

Bach’s objections from absent-minded, instinctive and impulive actions [??]

Frankfurt’s View

Action is ‘behaviour whose course is under the guidance of an agent’.

Two Problems:

What is guidance?

When is guidance ‘attributable to an agent’?

Consider that the spider’s movements walking on the web are guided by the web’s structure.

And similarly for your actions when driving on the roads.

(Guiding is not only something you do, but something that is done to you.)

Ok, so that’s why we’re asking the question ...

[Frankfurt] Do spiders have intentions?

[Bach] When I duck to avoid a flying object, am I acting on any intention?

There are theoretically coherent ways of characterising intention on which the answers are yes.

There are theoretically coherent ways of characterising intention on which the answers are no.

How can we decide between competing views which are both theoretically coherent?

p Two part solution

p 1. kinds of explanation

p 2. contrast Frankfurt with Bach (intentions might guide; potentially false opposition because causing and guiding; what view we take should depend on how the explanations go)

p Tuebingen: Is science relevant?

p.indent distinguish How do people ordinarily make the distinction (perhaps in myriad ways) from how could we make a systematic and explanatorily useful distinction?

p.indent philosophers are studying neither

p.em-above Bochum kinds of explanation (primary motivational states)

p.em-above Point is that once we understand explanatory frameworks, we can get a fix on the distinctions Frankfurt/Spiders and Bach/ducking are aiming to capture with mere guesses.

\section{Are scientific discoveries relevant?}

Donald Davidson asks, ‘What is the mark that distinguishes ... actions?’ Are scientific discoveries relevant to answering this question?

Q1

Donald Davidson asks, ‘What is the mark that distinguishes ... actions?’ Are scientific discoveries relevant to answering this question?

Q2

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

Q3

How are non-accidental matches between intentions and motor representations possible?

informally observing,

guessing (‘intuition’),

imagining counterfactual situations

(‘thought experiments’),

reasoning,

& pursuing theoretical elegance

First, think about the methods philosophers use.

Am I missing any?

Next, think about how philosophers construct theories of action ...

Here’s Ayesha and she’s about to act, which involves some kind of

processes occurring in her imnd.

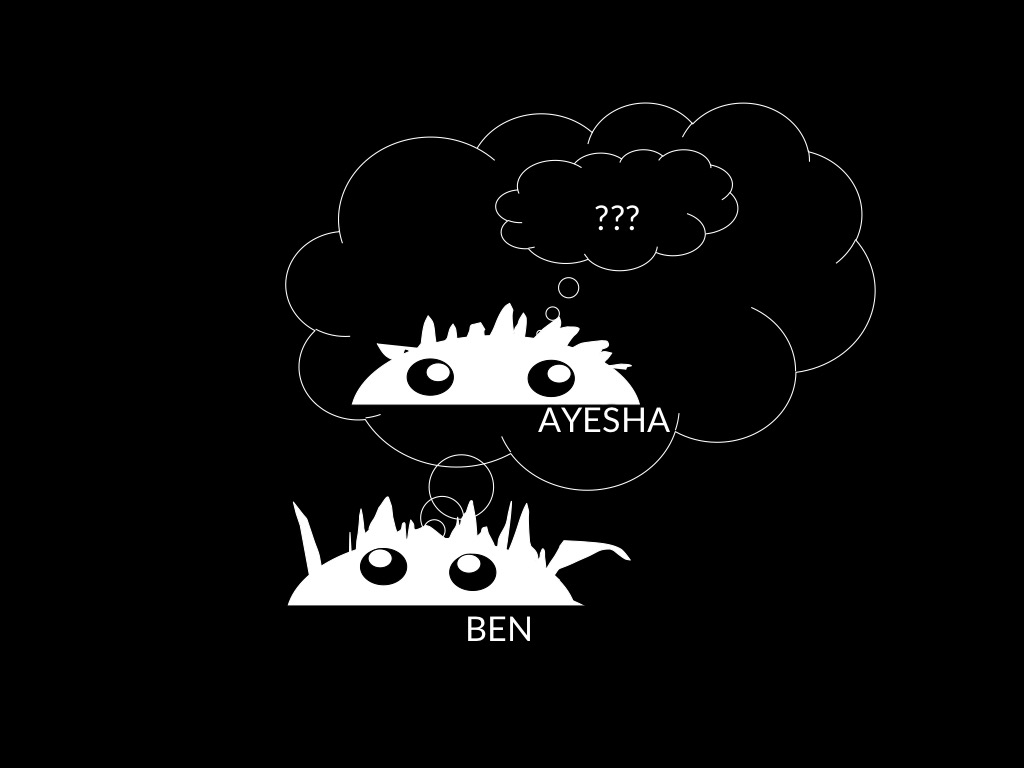

Ben want’s to predict Ayesha’s action, perhaps so he can coordinate his actions

around hers. He is therefore having a think about what Ayesha might be up to.

Implicit in Ben’s thinking is a model of actions.

And along comes the philosopher and attempts to guess what is going on in

Ben’s mind when he is thinking about Ayesha.

The philosopher asks, in effect, What model of actions is implicit in Ben’s thinking?

And this, essentially, is the raw material for philosophical theories of actions.

Focus on Ben for a moment.

What mundane purposes does thinking about actions serve?

\begin{itemize}

\item prediction and coordination

\item ethical (assigning responsibility, blame; living together)

\item normative (how actions should be)

\item regulative (he wants himself and others to live it out as much as to describe how things are)

\end{itemize}

Insofar as thinking about actions enables making predictions,

how accurate would we expect it to be?

So it’s not all about accuracy; in fact, of these, only prediction and coordination even

potentially requires that his model of actions is accurate.

Functions of Ben’s model of minds and actions:

- ethical

- normative

- regulative

- predictive

Second, consider Ben’s concern with making predictions.

--- speed vs accuracy

Whenever you are making predictions about anything at all, you face a

\textbf{trade-off between accuracy and speed}.

Making more accurate predictions requires considering more information and integrating

it in a more complex model of minds and actions.

By contrast, making faster predictions requires narrowing the information you consider

and using a less complex model of minds and actions.

Since an observer often has to make predictions fast enough to actually coordinate her actions

with another agent’s, and since making predictions consumes scarce

cognitive resources, the observer usually needs to trade accuracy for speed.

Because making predictions involves a trade-off between speed and accuracy,

we should not expect mundane thinking about actions to be especially accurate.

So Ben’s model of minds and actions is not built for accuracy.

So this is the model of minds and actions on which many philosophical theories

are based ... they are cast as attempts to characterise this model.

Maybe philosophers are not interested in the mark of action but in how

people think of action.

How do people ordinarily make the distinction between actions

and other events in an agent’s life? Perhaps in myriad ways.

But if philosophers were really interested in this, they’d be using the

methods of social psychology. Which they are not.

Relying on philosophers to characterise actions

would be like

relying on Aristotelians to characterise physical objects.

In the case of physical objects, I suppose few people seriously think

there is much we can understand without appeal to physics.

As Newton stressed, contemporary philosophical methods are not well suited to the task.

Contemporary philosophical methods are of limited use in making discoveries about the world.

Q1

Donald Davidson asks, ‘What is the mark that distinguishes ... actions?’ Are scientific discoveries relevant to answering this question?

Q2

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

Q3

How are non-accidental matches between intentions and motor representations possible?

So I was asking whether scientific discoveries are relevant ot answering Davidson’s

question, ‘What is the mark that distinguishes ... actions?’

My conclusion is that PHILOSOPHICAL THEORIES ARE NOT LIKELY TO BE RELEVANT to answering

the question.

Because philosophical methods are of limited use in making discoveries about the world.

Ultimately, the scientific discoveries are our only hope.

So why would philosophers think about Davidson’s question at all?

One thing philosophical methods are ideally suited to is

identifying limits on scientific theories and asking questions.

Not knowing things is what philosophers are best at.

This brings me to my next question ...

\section{Two Kinds of Motivational State}

motivational states

Preferences are one kind of motivational state.

These states change under the influence of data-driven learning and fashion, among other things.

I prefer chocolate over rhubarb right now, but might later have the reverse preference.

When we think about motivational states, the most familiar kind is ...

primary motivational states

not directly modifiable by learning

- hunger

- thirst

- lust

- disgust

- ...

... preference. These states change over time in under the influence of learning (and fashion, ...)

I prefer chocolate over rhubarb right now, but might later have the reverse preference.

preferences

changing, influenced by learning (and fashion, ...)

- chocolate over rhubarb

- lime over lemon

- red over blue

- ...

Another kind of motivational state is what animal learning theorists

call ‘primary motivational states’.

These are not modifiable by data-driven learning (nor fashion),

or at least not readily modifiable.

They inlcude hunger, thirst, lust and disgust.

Can your primary motivational states diverge from your preferences?

Premises

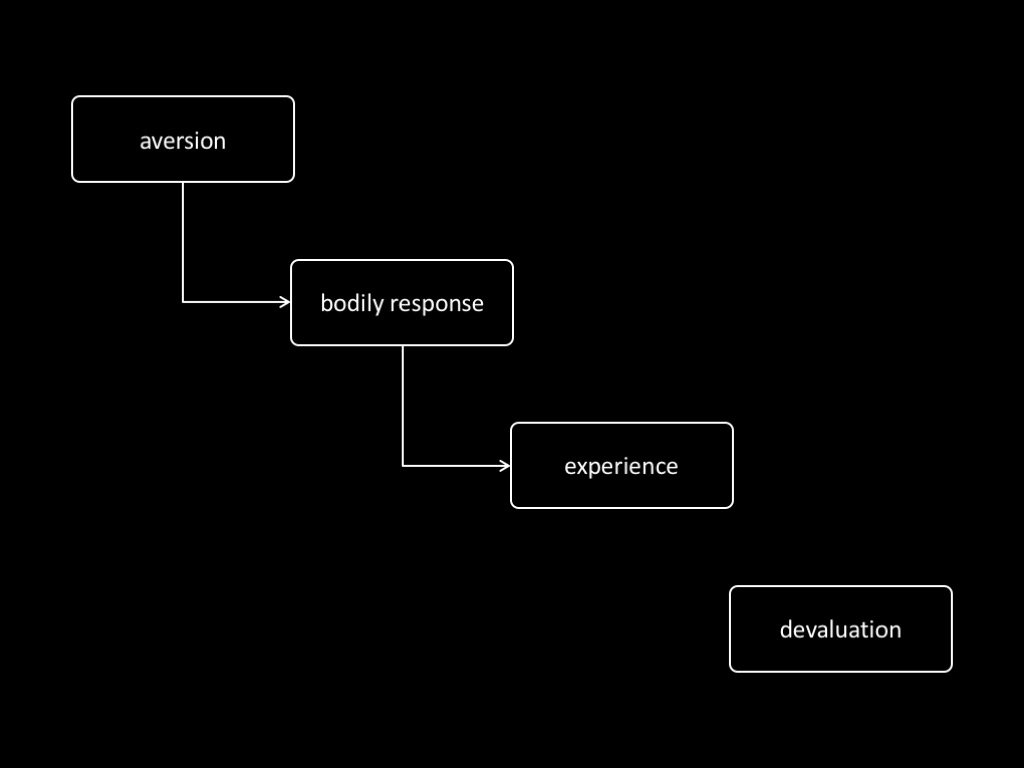

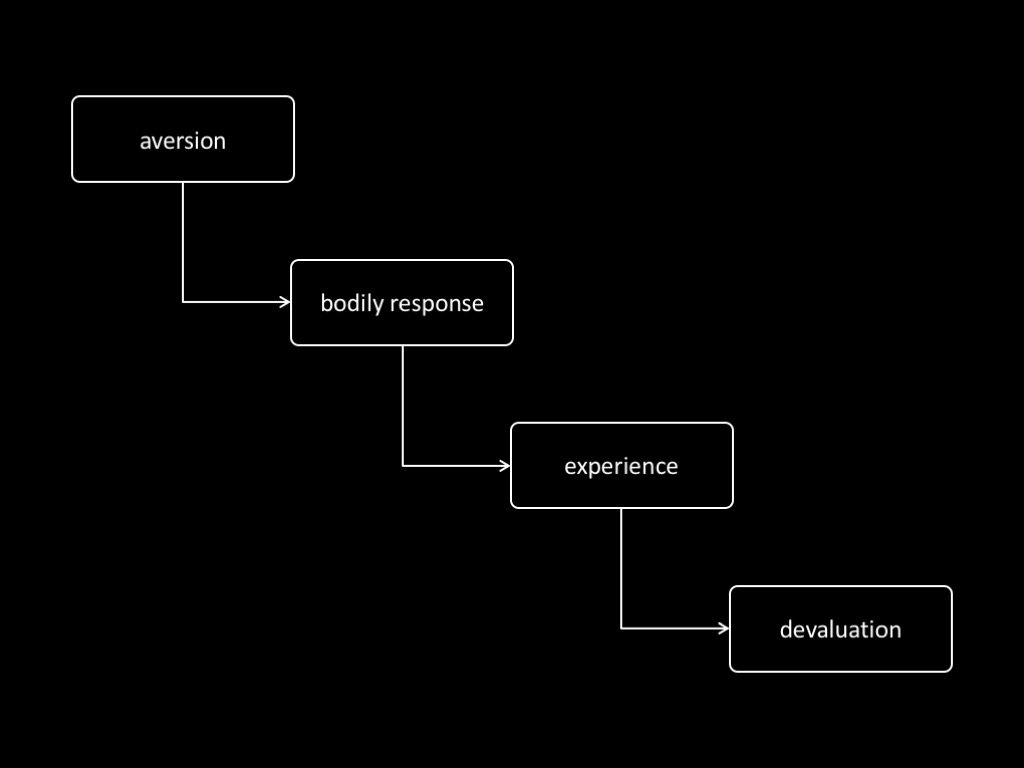

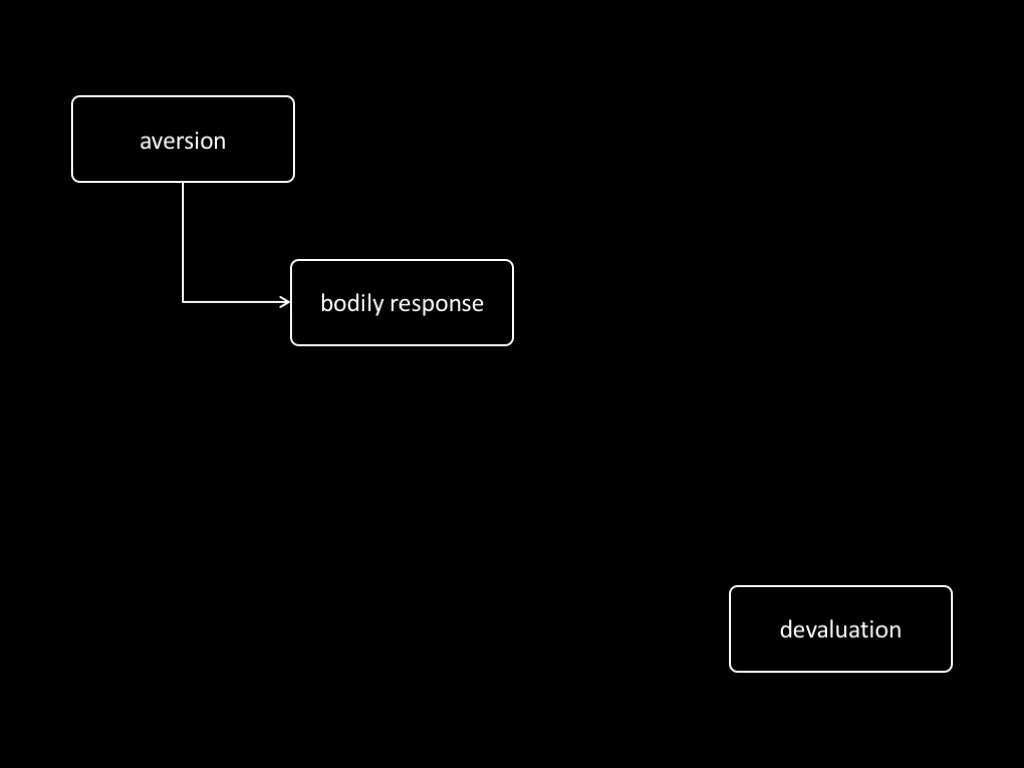

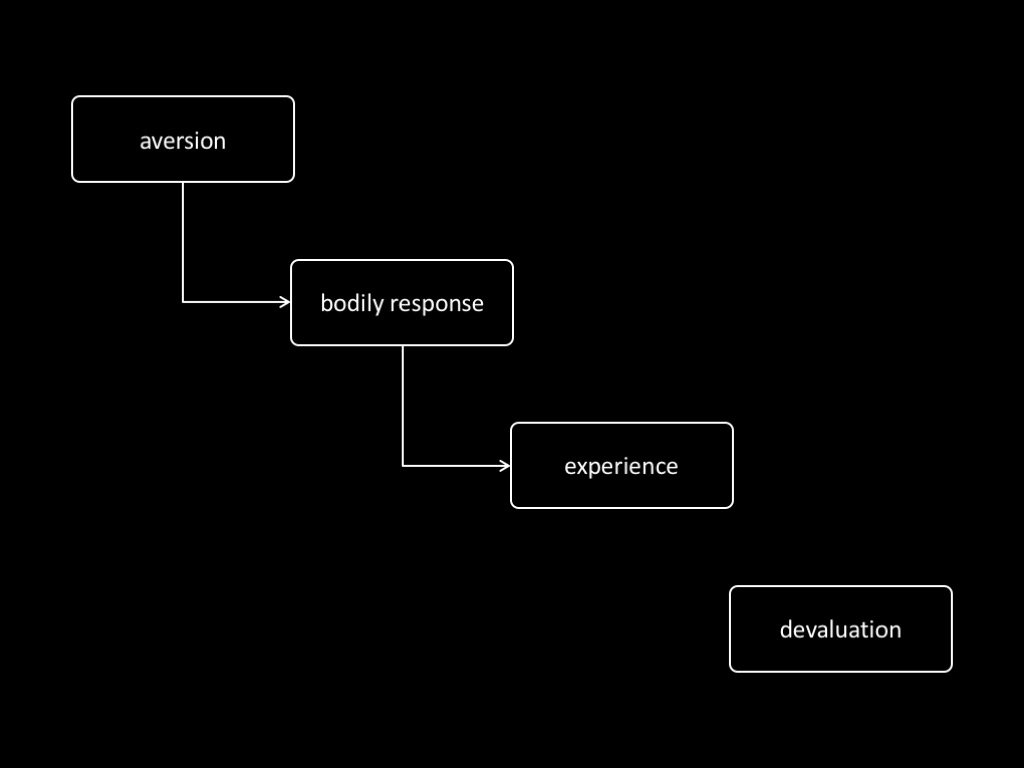

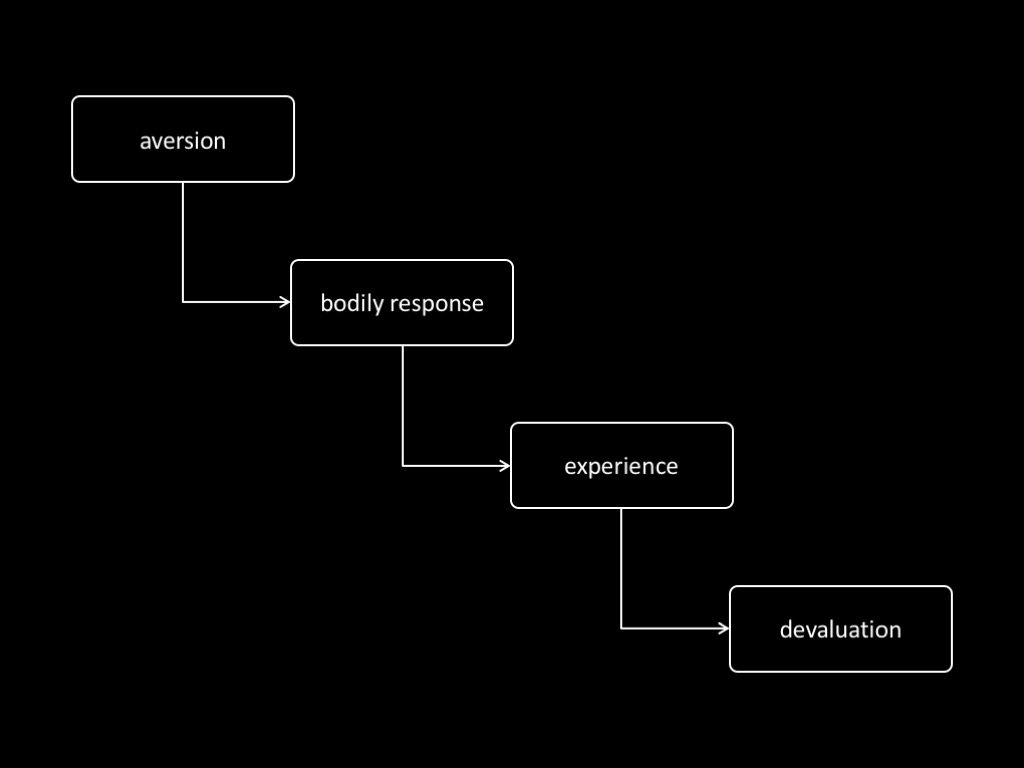

1. Toxicosis directly influences only primary motivational states.

2. Primary motivational states directly influence only stimulus-driven actions.

To a first approximation, the \emph{stimulus-driven} actions are those

actions formed in the presence of stimuli because of the stimuli’s presence (not

driven by representations of the stimulus).

You see a rat and a lever.

The rat presses the lever occasionally.

Now you start rewarding the rat:

when it presses the lever it is rewarded with a particular kind of food.

As a consequence, the rat presses the lever more often.

\subsection{Devaluation - standard procedure}

\begin{itemize}

\item Training: Rat is put in chamber with Lever; pressing Lever dispenses sucrose (novel food).

\item Devaluation: Rat is taken into another chamber, poisoned,

and then exposed to sucrose.

\item Extinction Test: Rat returns to chamber with Lever; pressing Lever does nothing.

\end{itemize}

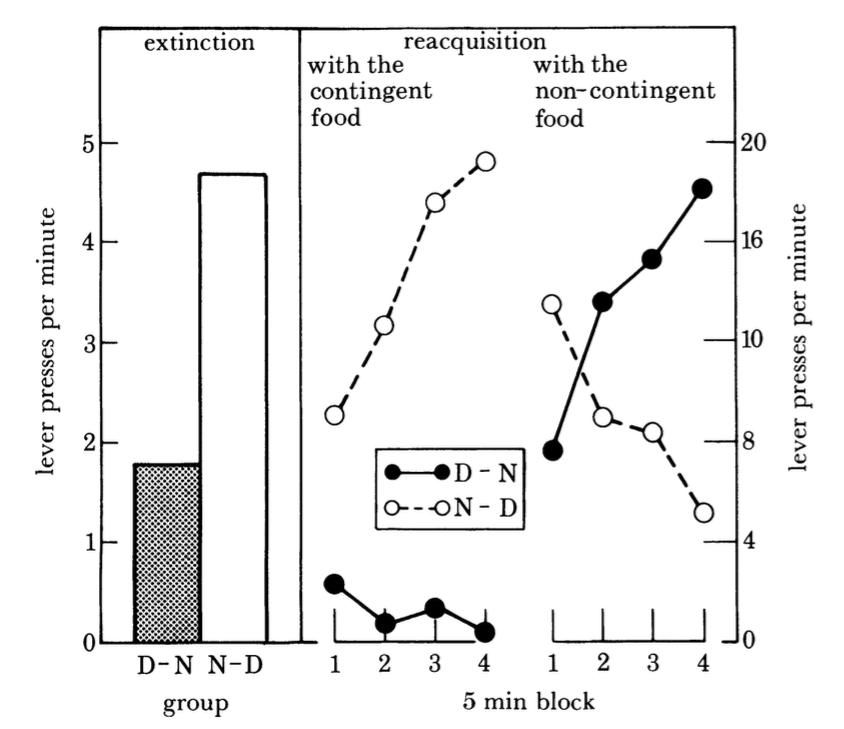

Dickinson, 1985 figure 3; Balleine & Dickinson, 1991 figure 1 (part)

Devaluation - standard procedure:

Training: Rat is put in chamber with Lever; pressing Lever dispenses sucrose (novel food).

Devaluation: Rat is taken into another chamber, poisoned, and then exposed to sucrose.

Extinction Test: Rat returns to chamber with Lever; pressing Lever does nothing.

Dickinson, 1985 figure 3; Balleine & Dickinson, 1991 figure 1 (part)

‘Mean lever-press rates during the extinction (left-hand panel) and reacquisition tests (right-handpanel) followingthe devaluation of either the contingent (group D-N) or non-contingentfood (group N-D).’

‘Experiment I: Mean number of lever presses ... during the extinction test session

...

The various groups received either immediate (Groups IMM/SUC and IMM/ H20) or delayed (Groups DELjSUC and DEL/H2O)

toxicosis [delayed did not cause aversion] and were re-exposed either to the sucrose solution (Groups IMM/SUC and DEL/SUC)

or to water (Groups IMM/H2O and DEL/H20).’

Pavlovain conditioning, primary motivational states can have a direct effect on actions.

Aversion does not directly influence preferences.

‘The pattern of results accords [...] with a role for an incentive learning

process in the reinforcer devaluation effect;

not only must consumption of

the reinforcer be paired with toxicosis,

the animals must also have an

opportunity to contact the reinforcer after aversion conditioning if there is

to be a change in instrumental performance’

\citep[p.~293]{balleine:1991_instrumental}

Balleine & Dickinson, 1991 p. 293

[To introduce the term ‘incentive learning’]

A moment ago I asked, What happens if we poison the subjects but do not re-expose them to the food?

Can your primary motivational states dissociate from your preferences?

The two kinds of motivational states can dissociate

primary motivational states

not directly modifiable by learning

- hunger

- thirst

- satiety

- disgust

- ...

preferences

changing, influenced by learning (and fashion, ...)

- chocolate over rhubarb

- lime over lemon

- red over blue

- ...

Experience is key ...

‘primary motivational states, such as hunger, do not determine the value of an instrumental goal directly;

rather, animals have to learn about the value of a commodity in a particular motivational state through direct experience with it in that state’

\citep[p.~7]{dickinson:1994_motivational}

‘primary motivational states have no direct impact on the current value that an

agent assigns to a past outcome of an instrumental action; rather, it appears

that agents have to learn about the value of an outcome through direct experience with

it, a process that we refer to as \emph{incentive learning}’

\citep[p.~8]{dickinson:1994_motivational}

Dickinson & Balleine , 1994 p. 7

A role for experience in solving the interface problem.

In rats (and humans), we can dissociate at least two kinds of states involved in causing actions.

Namely, preferences and primary motivational states.

These are linked to distinct processes, and distinct patterns of explanation (both of which involve justifying reasons of one or another kind).

Intentions (as well as beliefs and desires) play a role in one pattern of explanation, but not in the other.

\begin{enumerate}

\item In entering the magazine, our rat is acting.

\item The rat’s action is driven by a primary motivational state and a stimulus (the sucrose solution).

\end{enumerate}

Therefore (from 2):

\begin{enumerate}[resume]

\item The rat’s action does not involve intention.

\end{enumerate}

Therefore (from 1 and 3):

\begin{enumerate}[resume]

\item Not all actions involve intentions.

\end{enumerate}

1. In not entering the magazine, our rat is acting.

2. The rat’s action is driven by a primary motivational state and a stimulus (the sucrose solution).

Therefore (from 2):

3. The rat’s action does not involve intention.

Therefore (from 1 and 3):

Not all actions involve intentions.

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

Davidson’s View

It is intention (or justifying reasons).

Objection:

Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders [??]

Bach’s objections from ... [??]

Steve’s objection from primary motivational states.

Frankfurt’s View

Action is ‘behaviour whose course is under the guidance of an agent’.

Two Problems:

What is guidance?

When is guidance ‘attributable to an agent’?

So has Frankfurt won after all?

[LATER: No because the category of action turns out to lack uniformity.]

A single binary contrast? Or a family of cases.

I suggest that in explaining guidance, we will have to appeal to

belief, desires and intentions in some cases.

But in other cases we will have to appeal to primary motivational states and stimuli.

So Frankfurt is mistaken to think that his approach contrasts with Davidson’s.

Aside: Even if this is right,

Frankfurt did make at least one important point: we have to understand the role of intentions

and continuing throughout actions; and if we can’t explain guidance by invoking intentions

(which perhaps we cannot)

then Davidson’s idea won’t work.

conclusion

In conclusion, ...

\section{Conclusion}

Different marks distinguish different kinds of action.

To find the marks, identify the patterns of explanation.