Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Q

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

‘The problem of action is to explicate the contrast between

what an agent does

and

what merely happens to him‘

Frankfurt, 1978 p. 157

Explanatory vs Justifying Reasons (Dretske again)

Explanatory Reasons

Mark: factive (must be true); no point of view.

Why did Steve arrive looking like that?

- Because the path was so muddy.

Why did the sign fall over?

- Because the path was so muddy.

Justifying Reasons

Mark: nonfactive (can be false); agent’s point of view.

Why did Steve walk to the party?

- Because he believed it would be more romantic.

Q

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

A.1

It is intention.

A.2

Actions are events for which there are justifying reasons.

Among all the considerations which are, or might be, explanatory reasons for an action, what determines which are (the agent’s) justifying reasons?

Why did you run?

Ayesha

Desire: I catch the bus.

Belief: Running is a way of arriving at the stop before the bus leaves.

Intention: I run to the bus stop.

Beatrice

Desire: I catch the bus.

Belief: Running is a way of geting the driver to wait by signalling my desire.

Intention: I run to the bus stop.

Among all the considerations which are, or might be, explanatory reasons for an action, what determines which are (the agent’s) justifying reasons?

It’s those of her beliefs which lead to her forming the intention which guides her action.

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

Davidson’s View

It is intention (or justifying reasons).

Objection:

Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders

Don’t Spiders Have Intentions?

Sam’s Objection to Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders

‘... concepts which are inapplicable to spiders and their ilk.’

Frankfurt 1978, p. 162

‘Many animals that do not have conceptual intentions flexibly exercise agential control. [...] Spiders very likely do not have them’

Buehler, 2019

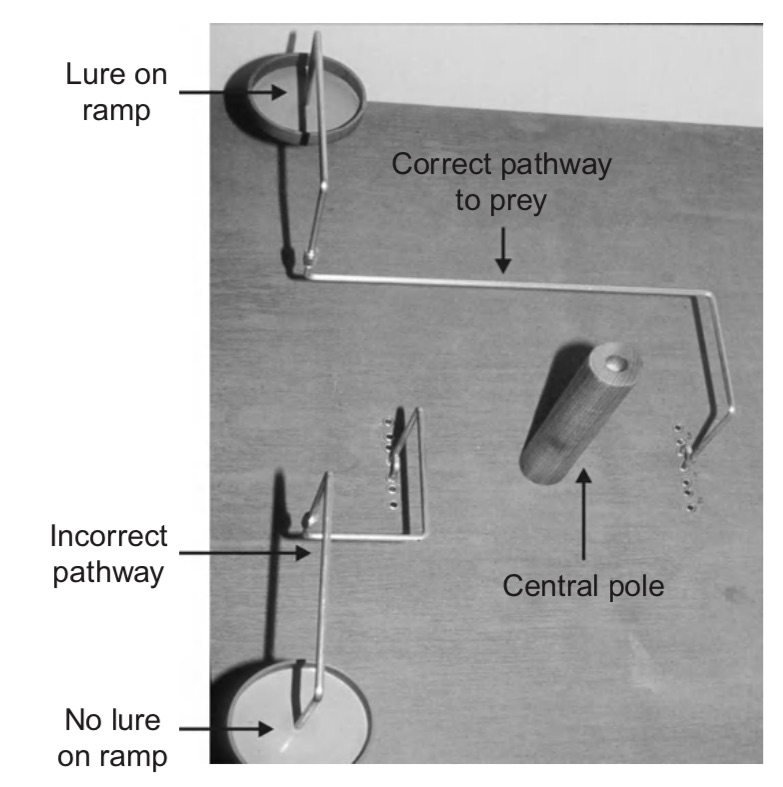

Jackson & Cross, 2011 figure 3

Jackson & Cross, 2011 figure 2

‘... concepts which are inapplicable to spiders and their ilk.’

Frankfurt 1978, p. 162

‘Many animals that do not have conceptual intentions flexibly exercise agential control. [...] Spiders very likely do not have them’

Buehler, 2019

never trust a philosopher

opinions

It’s not about you.

1. There is a contrast between actions and mere happenings in the lives of spiders.

2. The contrast in the lives of humans is the same.

3. Spiders do not have intentions, nor do they deliberate about what to do.

Therefore (from 1 & 3):

4. The contrast in the case of spiders cannot be explicated by appeal to intention.

Therefore (from 2 & 4):

5. The contrast in the case of humans cannot be explicated by appeal to intention.

Options:

try a different line

switch animals

further explicate the notion of intention

intentions as elements in plans

vs

representations which somehow guide actions

‘... concepts which are inapplicable to spiders and their ilk.’

Frankfurt 1978, p. 162

‘Many animals that do not have conceptual intentions flexibly exercise agential control. [...] Spiders very likely do not have them’

Buehler, 2019

Options:

try a different line

switch animals

further explicate the notion of intention

intentions as elements in plans

vs

representations which somehow guide actions

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

Davidson’s View

It is intention (or justifying reasons).

Objection:

Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders

Options:

try a different line

switch animals

further explicate the notion of intention

intentions as elements in plans

vs

representations which somehow guide actions

‘some actions are performed too automatically, routinely, and/or unthinkingly to be in any way intentional.

There need be nothing intentional about scratching an itch [...]

There need be nothing intentional about [...] ducking under a flying object.

Impulsive actions are not intentional’

Bach, 1978 p. 363

1. Ducking under a flying object is an action.

2. When you duck under a flying object, there is no intention you are acting on.

Therefore:

3. Intention is not the mark that distinguishes actions.

conclusion

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

Davidson’s View

It is intention (or justifying reasons).

Objection:

Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders

Bach’s objections from absent-minded, instinctive and impulive actions [??]

Frankfurt’s View

Action is ‘behaviour whose course is under the guidance of an agent’.

Two Problems:

What is guidance?

When is guidance ‘attributable to an agent’?

next theme: suicide

Frankfurt’s Further Objections to Causal Theories of Action

Frankfurt’s Objection from Knowledge

‘Causal theories imply that actions and mere happenings do not differ essentially in themselves at all.’

‘They are therefore committed to supposing that a person who knows he is in the midst of performing an action cannot have derived this knowledge from any awareness of what is currently happening, but that he must have derived it instead from his understanding of how what is happening was caused to happen by’

Frankfurt, 1978 p. 157

How can we individuate events? By their causes and effects.

Objection: Couldn’t an event have had effects other than those it actually had?

I was unlucky. That shot might not have killed him.

Reply: no.

Frankfurt’s Objection from Knowledge

‘Causal theories imply that actions and mere happenings do not differ essentially in themselves at all.’

‘They are therefore committed to supposing that a person who knows he is in the midst of performing an action cannot have derived this knowledge from any awareness of what is currently happening, but that he must have derived it instead from his understanding of how what is happening was caused to happen by’

Frankfurt, 1978 p. 157

Frankfurt’s Objection from Deviant Causal Chains

‘No matter what kinds of causal antecedents are designated as necessary and sufficient for the occurrence of an action, it is easy to show that causal antecedents of that kind may have as their effect an event that is manifestly not an action but a mere bodily movement’

Frankfurt, 1978 p. 157

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

Davidson’s View

It is intention (or justifying reasons).

Objection:

Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders

Bach’s objections from absent-minded, instinctive and impulive actions.

Frankfurt’s View

Action is ‘behaviour whose course is under the guidance of an agent’.

Two Problems:

What is guidance?

When is guidance ‘attributable to an agent’?

Strong claim: To be an action is to be caused by an intention.

Weak claim: To be an action is to stand in some specific, but here unspecified, relation to an intention.

Frankfurt’s Objection from Deviant Causal Chains

‘No matter what kinds of causal antecedents are designated as necessary and sufficient for the occurrence of an action, it is easy to show that causal antecedents of that kind may have as their effect an event that is manifestly not an action but a mere bodily movement’

Frankfurt, 1978 p. 157

Frankfurt’s Objection from Being in Touch

‘... the most salient differentiating characteristic of action: during the time a person is performing an action he is necessarily in touch with the movements of his body in a certain way, whereas he is necessarily not in touch with them in that way when movements of his body are occurring without his making them.

‘A theory that is limited to describing causes prior to the occurrences of actions and of mere bodily movements cannot possibly include an analysis of these two ways in which a person may be related to the may occur when an action is being performed or movements of his body. It must inevitably open the possibility that a person, whatever his involvement in the events from which his action arises, loses all connection with the movements of his body at the moment when his action begins.’

Frankfurt, 1978 p. 158

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

It is intention (or justifying reasons).

Objection:

Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders

Bach’s objections from absent-minded, instinctive and impulive actions.

Frankfurt’s View

Action is ‘behaviour whose course is under the guidance of an agent’.

Two Problems:

What is guidance?

When is guidance ‘attributable to an agent’?

‘A theory that is limited to describing causes prior to the occurrences of actions and of mere bodily movements cannot possibly include an analysis of these two ways in which a person may be related to the may occur when an action is being performed or movements of his body. It must inevitably open the possibility that a person, whatever his involvement in the events from which his action arises, loses all connection with the movements of his body at the moment when his action begins.’

Frankfurt, 1978 p. 158

‘... the most salient differentiating characteristic of action: during the time a person is performing an action he is necessarily in touch with the movements of his body in a certain way, whereas he is necessarily not in touch with them in that way when movements of his body are occurring without his making them.

Frankfurt’s mistake?

‘According to causal theories [...] the essential difference between events of the two types [actions vs things that merely happen to an agent] is to be found in their prior causal histories: a [pattern of joint displacements and bodily configurations] is an action if and only if it results from antecedents of a certain kind.’

Frankfurt, 1978 p. 157

Contrast Frankfurt, 1978 with Bach, 1978

‘though attempting to account for how action is initiated, they fail to deal with how it is executed. Nevertheless, I believe Causalism to be fundamentally correct’

Bach, 1978 p. 361

conclusion

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

Davidson’s View

It is intention (or justifying reasons).

Objections:

Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders

Bach’s objections from ...

Objection from Knowledge

Deviant Causal Chains

Being in Touch

Frankfurt’s View

Action is ‘behaviour whose course is under the guidance of an agent’.

Two Problems:

What is guidance?

When is guidance ‘attributable to an agent’?